The participation of women during the Spanish Civil War much like, women’s involvement here in the period surrounding the 1916 rising and war of independence has in many way been downplayed or outright ignored.

These backlashes and rewriting of struggles are depressingly common and generally follow when women or any oppressed group have gained ground – a reversion to the status quo. In both Spain and Ireland catholic institutions and practices were used to place a stranglehold on women’s rights. Fascist Spain offered celebration of “Nationalist Womanhood” and “mother of the nation” type traditional and repressive sensibilities while Ireland had the “special place” of women in the home enshrined in the constitution.

The destruction of republican materials as well as the imprisonment and execution of Republicans ensured the defeat of the republic but played a role in cementing the place of women with republican women particularly targeted in the aftermath of the war. Women in this fascist Spain were to go back to playing the part of the quiet “indoor heroine”, behind closed doors and out of public life.

To put this in perspective, from 1931 to 1936 Spanish women moved from one of the most traditional and patriarchal societies in Europe to being equal to men in the eyes of the law. They could vote, run for parliament, sign contracts, act as legal witnesses and guardians as well as get divorced. The second republic was trying to challenge gender bias and the oppression of women from the outset. The role that women played in combat during the Civil War is indicative of the massive changes happening in gender roles in the Republican zone. These changes were a necessity of the war but also a pivotal part of the social revolution that was taking place.

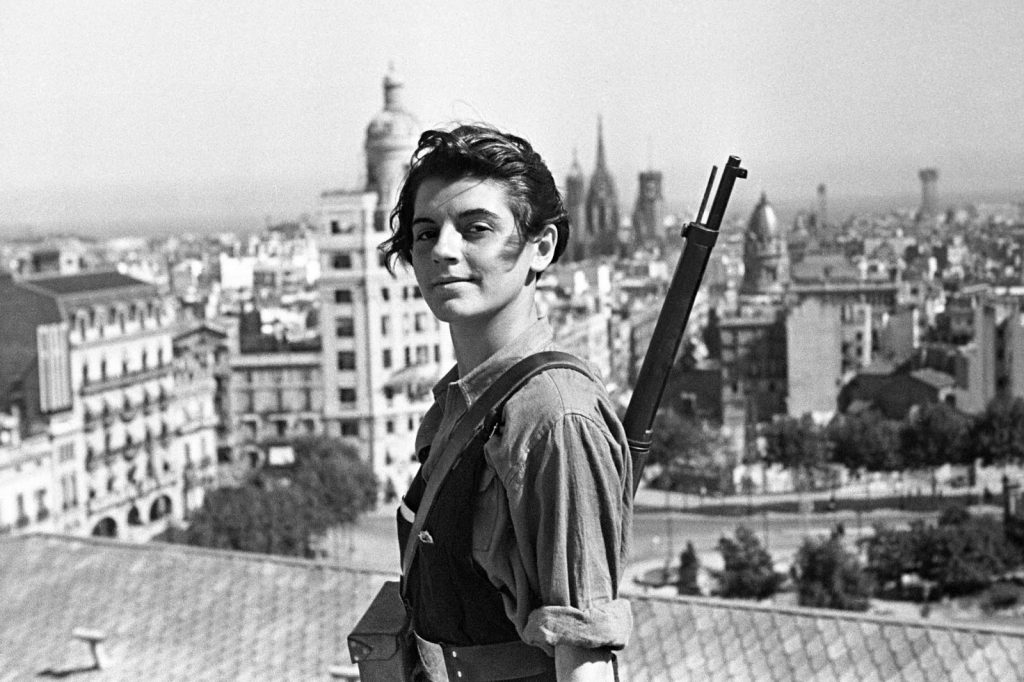

Militia women (Miliciana’s) were present in communist, anarchist, POUM and Republican Army units and they fought on the front lines and defended their own towns and cities as part of the rear guard. Front line women were generally integrated into the Republican force as members of mixed-gender battalions and moved around Spain depending on the needs of the conflict.

While gender roles were changing, they had not been completely revolutionised yet, true equality had not been achieved, it was a work in progress. Certain traditional and sexist attitudes held on in Spanish society and even among members of the Republican militias and left-wing political groups. That all being said the presence of women in the militia’s and the fact that they could and did gain leadership positions in several militia’s did much to challenge these views.

Lina Odena was one such example, a young communist activist and member of the national leadership of the United Socialist Youth, she was a leader of the anti-fascist resistance from the start. Through her efforts and dedication she achieved the post of commandant. Odena died on the Granada front after she and a comrade were discovered by Nationalists while on a reconnaissance mission. Odena, down to her last bullet, chose to shoot herself to protect her comrades. Interrogation by the Francoists was brutal, rape and torture would have awaited her. Her story was shared by the left wing and republican press cementing her place as a Republican war hero.

The Basque anarchist Casilda Méndez initially recorded that she did the cooking for her unit while being involved in other military tasks. Later, she moved to the Aragon front where she noted women had a greater level of equality and that their identity changed from ‘woman’ to ‘combatant’.

Not all militia women identified themselves in political terms and while there were long-time political activists involved in the Republican struggle, for many the fight against fascism was their initial foray into political activism. During this time many feminist and women’s organisations took the opportunity to push the advancements women were making. They did not see their liberation as a gift to be given to them but something that only they themselves could secure. There are countless stories recorded by the women of the time who had joined up with male family members, husbands, boyfriends and male friends, often with the aim to support them. These women went from wanting to be auxiliaries to fully fledged republican fighters in their own right. Women who learned to carry and fire a gun and were proud of it.

This burgeoning feminist mindset was present in many of these women who were seeking liberation for Spain, Catalonia, Galicia, but also for themselves. They could climb the ranks in the militias, lead men and their sacrifices were as great, if not more so to the cause.

Not all left forces were supportive of this type of active republican woman. Notably the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party rejected the notion of the radical woman. The only acceptable role for a woman to play was a ‘home front heroine,’ centred on civil resistance, everyday survival of the population, and carrying out voluntary relief work. It’s stark to note that this was the same way that the Francoists viewed and treated women roles – secondary and and in the private sphere. Given the PSOE’s lack of attention to gender issues, it is not surprising they took this approach but it must also be a lesson to us in the continued need to challenge ourselves and our own internalisation of capitalist and sexist norms.

So while the majority of women on the front lines participated in combat on equal terms with men; as noted by Mendez they also often suffered the double burden – they were expected to carry out “women’s work”; cooking, cleaning, laundry, sanitary, medical and political work. In some cases, these tasks were carried out by men and women equally, particularly in militias led by women, but in most cases, it revered to traditional gender roles.

The women of the militias when recording in diaries or reporting on this focus on the unfairness of it and the complicity of fellow comrades in their discrimination. There is a story that did the rounds at the time of two young women seeking to transfer to The Pasionaria, one of the units led by a woman where all work was divided equally, giving their reasons to transfer as “I did not come to the front to die for the revolution with a dish cloth in my hand”.

Paradoxically, independent Republican press at the time presented the housekeeping by the women in a very positive light. Newspapers such as La Voz and ABC published photographs depicting women fighters cooking, cleaning, washing and sewing, as their natural role and with a “Sure, aren’t they great girls” air about them.

Things were a little different for those in the rear guard, these milicianas were far more numerous and more visible to the rest of Spanish society than were the women stationed at the front. They were models of changing and evolving gender roles and prove that women’s military participation was a part of everyday life in the Republican zone. Those in the rear-guard were largely organised into women-only battalions and remained living in their homes playing a defensive role when the battle came to their cities and towns.

Madrid is the most prominent example of rear-guard women participating in combat. Catherine Coleman reports that thousands of women took an active part in the defence of Madrid. Among these were the Girls’ Union, a communist youth group of two thousand women aged fourteen to 25 who had been undergoing arms training and target practice since the outbreak of the war. This group were reported to be the last to retreat during the Battle of Madrid but it is rare to find them included in general histories of the siege.

The women’s stories, records and histories that I’ve referenced have been placed off to the side, often in favour of the classic male hero. These women were warriors and in many ways were the backbone and the face of the republican and anti-fascist struggles in Spain. There stories need to be heard and it is our duty and responsibility as comrades, whatever shade of red, to remember and honour them by continuing the struggle, la lucha continua!

by L. Duggan, CPI

Pingback: Red News | Protestation