This article is part 2 in the first CYM Education Series: “Lessons of History”. Its origins are in a reading group for Connolly’s 1910 pamphlet “Labour in Irish History” based around a reading group for the Belfast branch of the CYM. Different members did reports on different chapters and given the consistent quality and relevance of the resulting output, this material has been adapted as our first Education Series series with the intention that a wider audience can benefit from an introductory guide to this seminal work on the making of the Irish working class.

RL, Béal Feirste

To understand An Gorta Mór’s affliction on the Irish people, and the rebellions that resulted, we must first explore the economic backdrop to conditions of the Irish peasantry and small urban proletariat within the context of the Act of Union of 1801 and the laissez-faire, classical liberal economic policy of the British government in the 19th century which constituted the Act.

Following the Act of Union, which brought Ireland into the United Kingdom, under one parliament there was a great decline in Irish industry, textiles in particular. Free trade was enshrined in Article 6 of the Act which brought Irish and British industrialists into direct competition. Before the Act, Britain had a protectionist economic policy in order to build up their own national industry before bringing it to competition on international markets. The capitalists of Britain were in a much better position to benefit from this “free enterprise” with their superior factory system, steam powered engines and richer supply of coal. Ireland’s coal reserves were far lower and Irish industrialists had been slow to adopt the changing technologies of the steam-powered engine and the factory system of production.

Furthermore, the Irish were crippled by British taxation, stifling any capital accumulation that could have occurred. Irish capitalists paid a disproportionate rate of tax in comparison to their British counterparts. This was in order to pay for the intensifying Napoleonic Wars between France and Britain. National debt in Ireland soared 250% in this period.

Now that we have tackled the industrial question in pre-famine Ireland, let’s look at agriculture. In this period, two-thirds of the Irish population relied on the land to survive, this serves to ramp up competition between tenant-farmers as more demand means higher rent. This reliance on the land and the potato crop was systematic and sponsored by the British government in order to drive down prices to feed the emerging British proletariat, this served to lower the labour costs of British industrialists. Ireland was the agricultural appendage of Britain. Let’s dissect the social relations that characterised the farmland in this feudal system. Irish landlords were often absentee, British aristocrats living in London or of the Protestant Ascendancy; middle class protestant aristocrats living in Ireland. This system of landlordism was sponsored by the state through the penal laws, and backed by the Church of Ireland, this important to remember for later.

Rents were often so high they absorbed any profit the tenant-farmer had made from selling his crop and much of the ”wage” that paid for food for his family. Thus, the tenant-farmer became directly reliant on the crop itself to feed themselves. This was accentuated by the Corn Laws of 1815 which favoured English grain, domestically produced to Irish grain. The barriers were simply too high for Irish grain to be sold into the English market under this legislation. This Irish landlordism was the most brutal and wretched form of landlordism imaginable, if the tenant-farmer improved the land through manuring the land, building fences or installing drainage systems, the landlord simply increased the rent. This ruined the productivity of the land and thus the crop it yielded. Landlords were also known to shorten the lease on the land if improvements had been made, meaning it could receive a higher price at the open auctions on the leases of the land. This drove many tenant-farmers to not improve the land and they would often destroy the property before the lease was finished, otherwise they would be outpriced in the auction for the lease, making them homeless and without income. The system of subdivision of land, each son being given an equal plot of land further exacerbated the crisis, leading to each family having less land, food and surplus with each generation. As a result, by 1841 40% of houses in Ireland were single-room mud cabins.

There was a class below that of the tenant-farmer or the smallholder: the unbound labourer. They usually paid half of the years rent at once of the 11 month lease and were made to work on small strips of land which had been pre-manured, in a conacre system of small allotments. They paid an inflated rent, and were essentially speculators, facing a profit from a good crop or financial ruin. The zero-hour contract bar staff of their era.

In the 1830s, amidst the growing poverty and starvation of the peasantry, they began setting up militant agricultural unions known as Ribbonmen, although they went under a number of names. They would prevent evictions by building barricades, destroying landlords’ estates and stealing their crops. However, the most antagonistic of their actions was the refusal to pay tithes. This began what was known as the Tithe War. Tithes were a yearly taxation, usually 10% of total earnings, made by the peasantry to the Church of Ireland. The RIC (Royal Irish Constabulary) and the British Army made evictions and burned crops in order to punish the peasantry or recuperate the losses on behalf of the church. The British Government introduced the Tithe Communication Act in 1838, which reduced its price and was added into rent instead of a fixed charge, however, Irish landlords were often too scared to ask for the tithe or asked only part of the charge for fear of reprisal.

So far, we have talked only about the legislative and the social factors in pre-Famine Ireland. Now let us talk about politics. The largest movement of political agitation in Ireland at the time was the Repeal Association, established by Daniel O’Connell in 1830 to repeal the Act of Union, O’Connell had been a key figure in the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 which redacted the Penal Laws. O’Connell spoke militantly in front of the peasants and often used violent language about national upheaval in order to repeal the Act of Union, this talk of “emancipation” pleased the fervent peasantry at the time. However, O’Connell was very much of the Catholic middle-class, and banned the speaking of Irish at his events which often had upwards of 100,000 in attendance. The “emancipation” O’Connell spoke of was neither social nor national. They wished to see not an Irish Republic as Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen fought and died for a generation before, but an Irish parliament within the Union, to protect the interests of the emerging Catholic middle class, landowners and industrialists after the repeal of the Penal Laws. The peasants soon learned this lesson. In one of his private letters O’Connell stated, “I desire no social revolution, no social change… In short, salutary restoration without revolution, an Irish Parliament, British connection, one king, two legislatures.” For us it is quite obvious to see that O’Connell was utilised by the political class in Britain in order to pacify the burgeoning revolutionary movement that was brewing in the peasantry.

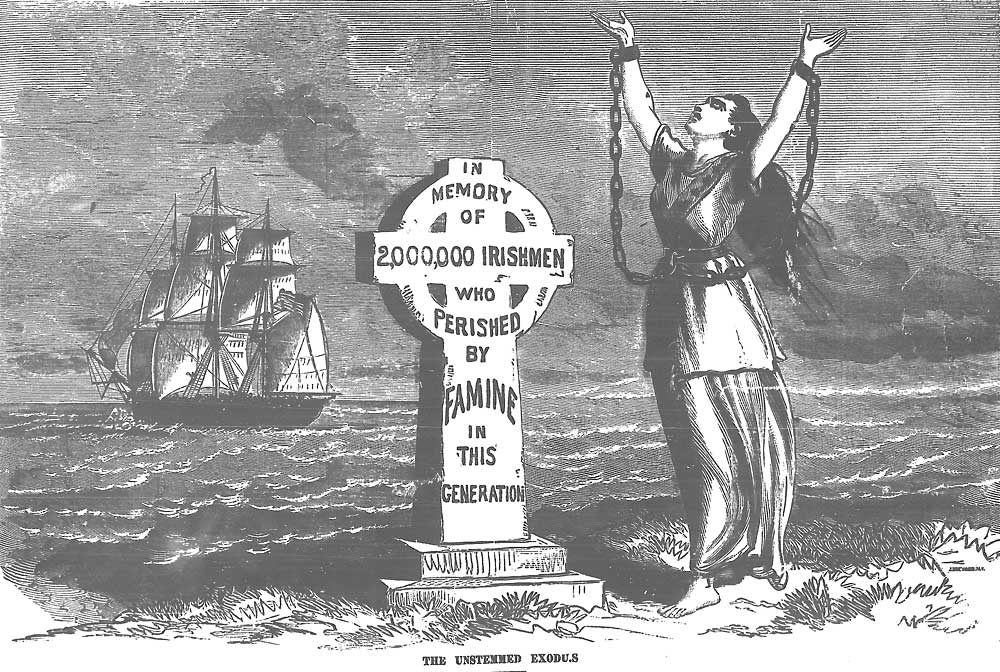

The potato blight struck in 1845 and lasted until 1849. Meanwhile massive shipments of grain were leaving the country. Tenant-farmers were forced off their land as they were unable to pay the rent and smallholders were forced to sell in order to feed themselves. Connolly estimated that the value of grain produced in 1848 was £44,958,120. Enough grain to feed the whole of Ireland twice that year. These mass land clearances made way for landlords to buy large swathes of land for cheap and use them for grazing cattle to feed the growing English proletariat in Britain. Through a Leninist analysis of the situationm communists can conclude that this was a concerted effort at changing the use of Ireland’s farmland from crop to cattle to keep labour costs down in Britain. All of this was enforced through violence and coercion by the state and its apparatus; the British courts, the Church of Ireland, the military and the police.

The Whigs came into power in 1846, close allies of the Repeal Association and they repealed the corn laws. This brought Irish grain now into direct competition with English grain in a free market, forcing the Irish grain producing peasantry to lower their prices while rent stayed the same. Many ate what they grew and were evicted for failure to pay their rent, facilitating the land clearances. 3,668,000 people were evicted from their homes between 1838 and 1888. The Whigs saw intervening in the “Irish situation” as impeding on their principles of the free market and that the markets would resolve themselves. In fact, giving relief would be “demoralising”. However, the Whigs gave in with drastic measures such as the Poor Relief Bill of 1847, which introduced relief houses in order to pay a wage to Irish peasants driven off their land who were fit enough to work. They were often seen as worse than prisons and many viewed them as a last resort. In order to not interfere with private enterprise, these relief houses only did unproductive labour, so not to interfere with the operations of the capitalist class of England who were ravaging Ireland’s resources while people starved. They built roads to nowhere and bridges over streams. Nonetheless, the workers had no use for money as no retail, domestic markets for food existed in rural Ireland at the time and the small local food markets had long vanished. In order to work in the houses every peasant had to give up their land over one-quarter of an acre. The English capitalist class acted solely in the interest of capitalist political economy and the social and intellectual fetters that came with it. The Irish people were sacrificed on the altar of private property and free trade.

Where was the “great liberator” of Ireland, O’Connell, during this? He advocated for non-violence. The Irish Confederation was formed as a result by members of the Young Ireland Movement they believed violence was necessary in order to emancipate Ireland. O’Connell tarnished them as enemies of the church and the people. In fact, the Irish peasantry were baying for revolution. The Young Irelanders of the Irish Confederation formed a new paper called The United Irishman in which increasingly politically-conscious analyses were being made, but alas little action.

John Mitchel synthesised the national and the social question at the time, just as Connolly and Lenin would later. He drew a scientific analysis of capitalism and free trade and its effect on the starvation of the Irish. “An insurrectionary upheaval that would end, the subjugation of the labouring classes would also end the tyranny of the British government that thrived on it.” They called for rent strikes and drew inspiration from the French Revolution which established the second republic in 1848, they published military tactics in their paper. Men like Mitchel and Lalor called for a social and a national revolution as one, to remove the foreign occupier and the foreign system imposed upon us in order to bring land ownership under the nation and provide food and employment for our people.

The people waited for the orders to rise up. John Mitchel was arrested and deported to Tasmania, unfortunately militant men like Mitchel were in the minority of the leadership. The peasants began acting spontaneously, burning bridges and rescuing the arrested leaders of the Young Irelanders, some handed themselves back into the arms of the state voluntarily. One leader, William Smith O’Brien told people to get ready for a revolt but to pay their rents and to give away their food. Ultimately, they too gave into the ideal of private property, many of them were landowners themselves. As Connolly said, “everything had to be done in a ‘respectable’ manner; English army on one side, provided with guns, bands, and banners; Irish army on the other side, also provided with guns, bands and banners, ‘serried ranks with glittering steel’, no mere proletarian insurrection, and no interference with the rights of property.”

Connolly went onto write in his Days of March one month before the Easter Rising:

The hurler on the ditch sees the most of the game because he is on the ditch, and not intent upon keeping his own end up in the place allotted to him on the field. So the student of history is wise, and can justly criticise the mistakes of men whose powers of judgment may nevertheless have been infinitely superior to his own. He may justly criticise their mistakes, but may also in the part he is playing in the historical crises of his own time be making mistakes a thousand times more serious and less excusable. The United Irishmen waited too long, the Young Irelanders waited too long, the Fenians waited too long. This is the opinion of every student of history worthy of the name. But who dare censure these brave men and women? Assuredly not the men and women of our generation. To us also a great opportunity has come. Have we been wise? The future alone can tell.

As students of history, as every Marxist-Leninist should be, we should uphold these legacies and learn from those who came before us so that, as Connolly hoped, when a great opportunity comes we will be wise.