SF, Gaillimh

On July 1st, we commemorate the inauguration of Kwame Nkrumah as the first president of an independent Ghana. A socialist revolutionary and Pan-Africanist, Nkrumah was one of the dominant figures in the wave of decolonisation that occurred following the Second World War.

Born in 1909, to a working class family in what was then the British-controlled Gold Coast, Nkrumah’s initial choice of profession was as a teacher. In 1935, following time as a school principal, Nkrumah travelled to the United States to pursue a Bachelor of Theology. While there, he became deeply involved in the Pan-Africanist movement in New York and was a major participant in the Pan-African Conference held there in 1944. The following year, he was involved in a similar conference held in Manchester, which he described as ‘a tremendous success, where both capitalist and reformist solutions to African problems were rejected’ (Hakim Adi, Pan-Africanism, p. 126).

The same year he returned to the Gold Coast and almost immediately became an important figure in the independence movement in both the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) and Convention People’s Party (CPP), roles that saw him imprisoned multiple times by colonial authorities. However, by 1952, he was prime minister of the Gold Coast, and would retain the position in the newly independent Ghana. In 1957, Ghana became the first African country to break free from European rule, and in 1960, Nkrumah was elected its first President, the first of many African socialist leaders to come.

Nkrumah’s thought was one of the central influences of what is today referred to as African Socialism. According to Nkrumah, it was ‘the ideology of the New Africa, independent and absolutely free from imperialism, organised on a continental scale, founded upon the conception of a one and united Africa, drawing its strength from modern science and technology and from the traditional African belief that the free development of one is the condition for the free development of all’. (quoted in Curtis C. Smith, Nkrumaism as Utopianism, 1991, p. 31). The dangers of neo-colonialism and his emphasis on the importance of African nations standing on their own two feet was to prove massively influential for other African revolutionaries such as Thomas Sankara, who echoed Nkrumah’s warnings on the dangers of foreign aid: ‘Aid to a neo-colonial State is merely a revolving credit, paid by the neo-colonial State and returned to the neo-colonial master in the form of increased profits’ (Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism, The Last Stage of Imperialism, p. xv).

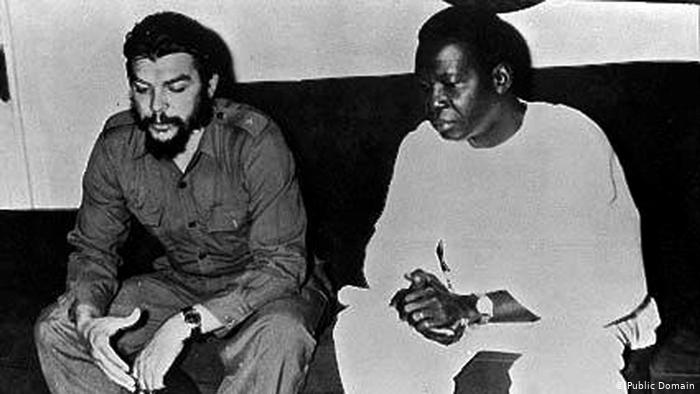

While agreeing with many aspects of Marxism-Leninism, Nkrumah emphasised certain differences. For instance, while the prevailing orthodoxy held that class revolution was the only way to achieve a socialist society, Nkrumah insisted that Ghana came, ‘directly from Engels’ primitive communism to socialism, and which has always had unity, never the disunity of separate classes and interests’ (Smith, p. 34). However, Nkrumah became more and more convinced of the necessity of revolution over reform, particularly following the Western-backed coup that forced him into exile in Guinea, where he was named honourary co-President.

His emphasis on decolonisation also allowed him to find parallels outside of Africa, such as in Ireland. At a meeting of the Irish United Nations Association in May 1960, on the eve of his presidential victory, Nkrumah paid tribute to ‘those Irish leaders of the last century who realised that the struggle of Ireland for independence was not the struggle of one country alone, but part of a world movement for freedom’ (Kevin O’Sullivan, Ireland, Africa and the End of Empire, p. 1).

Further Reading:

Kwame Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism and Africa Must Unite

Kwame Nkrumah, Class Struggle in Africa

Hakim Adi, Pan-Africanism: A History

Kevin O’Sullivan, Ireland, Africa and the End of Empire: Small State Identity in the Cold War, 1955-1975.