This month marks 11 months of the Connolly Youth Movement’s occupation of a formerly derelict building in Cork City Centre. Throughout this piece I will attempt to illustrate both my own personal affinity with the project and the implications that I believe actions such as this can have on both a regional and national scale.

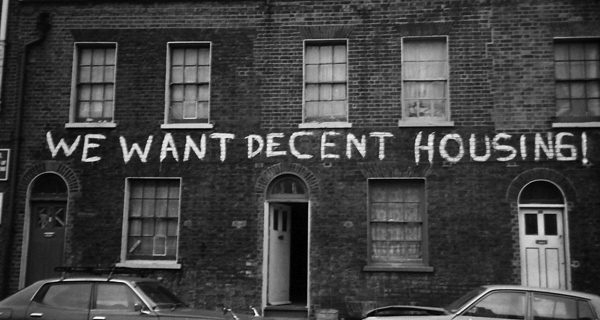

When the Cork branch of the movement first had the idea to liberate an idle building, it stemmed from the knowledge that Ireland as a nation currently faces its worst housing crisis since the formation of the state. There are now well over 10,000 people homeless in Ireland. Roughly a quarter of those residing in emergency accommodation are families, meaning over 3,000 children in the country not having a place to call their home. The main political parties have little to no interest in addressing this problem. Against the advice of community activists and economists alike, the party in government for the last 7 years, Fine Gael, has allowed economic evictions to continue unperturbed, mortgage repossessions to happen in huge numbers, and rents to skyrocket out of control and beyond the affordability of large numbers of citizens. During November last year, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar attempted to diminish the gravity of the crisis by saying that homelessness figures were ‘low by international standards’, a lie for which he has come under fire by charities such as the Simon Community. Efforts to compare international figures are generally impeded by the problem of different definitions applying in each country, but even an attempt to overcome this shows that at least five different ‘peer countries’ have a much better handle of the problem than Ireland currently does. Furthermore, this comparison is based on figures from 2014. Since then, national adult homelessness figures have more than doubled, the figures for children have quadrupled. Hidden homelessness lies beneath society’s gaze and some of the most appalling poverty and instability is experienced by those surfing couches without a clear end in sight.

It was decided by group consensus that direct action had to be taken in order to meaningfully attack the fundamental root of this problem, rather than its symptoms. After identifying it as the best course of action we began to identify local buildings which had been noticeably idle for some time. In the end, we chose a house which we knew to have been left unused for a duration of eight years. It goes without saying that it was not immediately fit for habitation. Years of dampness and cold had led to mildew covering many of the walls, cobwebs on the ceilings and dust so thick it would leave a footprint after stepping on it.

Despite first appearances, through coordination were able to transform the house from a state of dilapidation into a home better than many which I have rented or shared in the past. Two members of the group moved in and two weeks later I followed suit. From the very start the aura in the house was one of tangible excitement and pride in what we had achieved. The building became a hub of vibrant community activity, on more than one occasion with us facilitating discussions with representatives of local and international leftist groups. We have hosted arts and crafts evenings where we have designed posters and placards which we have used at various protests. We have created an atmosphere of independence and interdependence, a commune in which we can meet to discuss and plan strategies that we feel will expose and counter the relentless assault of neoliberal policies on the poorest of our community. The house has also served as a temporary safety net for those suffering the consequences of resulting precarity.

An obvious issue has to be addressed here. Occupying an idle or derelict building under present conditions is not a long-term solution, neither for ourselves nor for society at large. The judicial system opposes the very essence of this demonstration of people’s power. Furthermore, landlords constantly use extrajudicial means in order to forcefully remove tenants from their home, often it may be somewhere a person has lived for decades, often it may be families with young children. The constitution as well as historical and recent legislature in this country have been written to protect power. The right to deny others access to unused housing, to exploit workers, to force the unemployed into slave labour, all co-exist in a country that tries to present a well-curated image of respectability. Our society is crafted along a singular basis – the channeling of wealth upwards and out.

In January of this year, in Dublin’s Mountjoy Square a man was hospitalised with severe bruising after his landlord, Paul Howard, employed several men to throw him and his family from their apartment despite a High Court ruling prior to Christmas that the matter was to be disputed by the Residential Tenancies Board. This happened as a result of Howard trying to illegally raise rent past the permissible amount decreed legally. Lugus Capital, a shell company who have recently acquired ownership of Cork’s Leeside Apartments are currently attempting to evict tenants from all 70 of the building’s apartments under the dubious guise of replacing fire doors. This claim has been contested by local councillors and activists as simply a means for profiteering landlords to exploit loopholes in legislation regarding rent pressure zone restrictions.

Predictably, on the sole occasion that we experienced a confrontation with the alleged owner of our own home, the two Garda detectives that were present did not request any deed to the house, ignored our insistence that this man had broken the front door’s lock before entering the property, and generally harassed both residents and those who showed up to defend the project. One of them even went so far as to threaten a branch member with arrest when they took it upon themselves to video the proceedings. All of this with the knowledge that they had no authority in our situation. Residents of the house as well as the branch in general welcomed this antagonism openly as we knew it to be instrumental in propelling the project squarely into the public gaze. Immediately we began to be openly questioned by representatives of local radio stations and newspapers about the project and the homelessness crisis. A Facebook post that detailed the events of that day reached over 40,000 people. A predominantly positive reaction ensued from members of the public that commented and messaged the page in the aftermath, showing without a hint of uncertainty an appetite for radical measures to be taken which place in the forefront those suffering from a socioeconomic nightmare not of their causing nor of their neglect.

Incidents like this are not isolated but are on the rise and will become increasingly commonplace as long as our society prioritises the right to private property above the right to housing. We believe the Irish Government should adhere to the principles of the UN Charter by enshrining the right to shelter into the Irish Constitution. The purpose of our occupation has three ambitions, short-term, mid-term and long-term. Short-term, that acts of organised community engagement in the political sphere such as Apollo House, Right2Change or even our very own ‘Connolly Barracks’ may inspire others to organise collectively with strategies that would help to put authorities under more pressure to allocate funds towards social housing. Midterm, that our project can eventually grow into an expanded network providing critical resources to working class youth which the state would prefer not to offer. Long-term, an objective re-evaluation of our political economy, who it is run by and in whose favour, and if indeed it is determined that it does not have the mandate of the people, what we may build in its place as an alternative. This would be a system not motivated primarily by financial gain in the form of profit but instead for the benefit of society at large, regardless of socioeconomic status in which housing as well as other basic services are not just treated as commodities but as basic human rights.

KC