LKL, Corcaigh

“If a radical feminist says to me that my work is an abomination, I say to her that all work is an abomination, and invite her to step down off her pedestal. I stand with her against the coercion, degradation, and fear that is undeniably present in some parts of sex work, but if she wishes to end it, let her stand with me against austerity, and the indignity of so much of the labour of women. Let her stand with me for decriminalisation.”

Magpie Corvid, “Marxism for Whores”

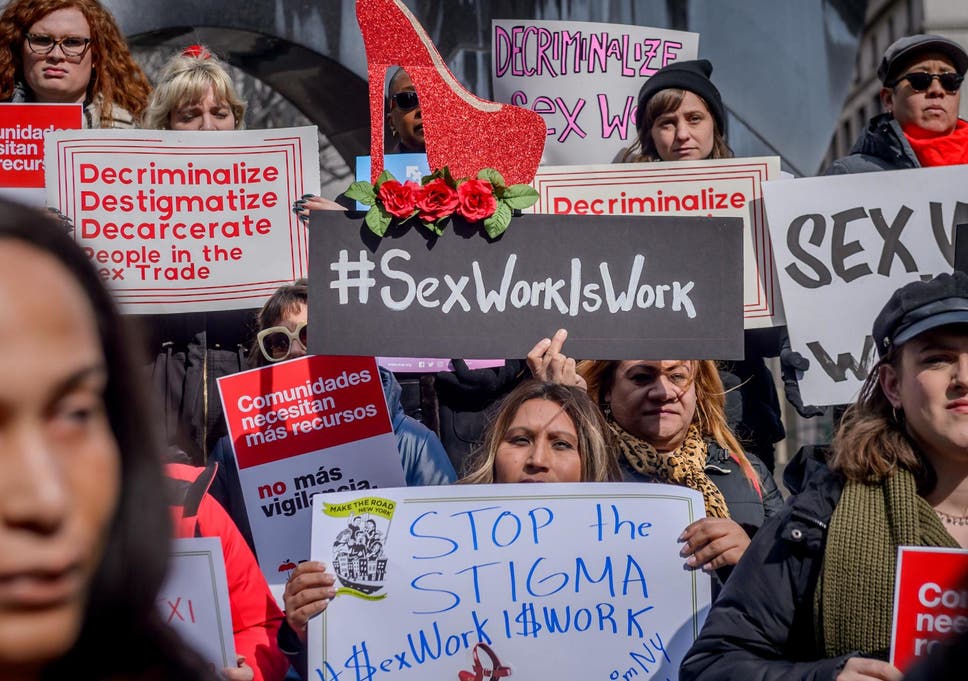

“The political history of sex workers is one of protest, is one of building our collective power, is one of standing in international solidarity, and of fighting back against the violence of the police. On International Whores’ Day and on every day we say #BlackLivesMatter.”

SWARM (@sexworkhive), June 2, 2020

Introduction

A recent article published in the Young Communist League’s Challenge magazine entitled “What is socialist feminism?” advocates for a Marxist feminist approach to women’s liberation, juxtaposed with the inadequacy of “radical feminism” and “liberal feminism”. The most glaring issues with this article are misguided and extremely harmful claims about sex work and the flippant dismissal of sex workers’ rights activism, namely the statement that “attempts to unionise [the sex] industry… have only sought to legitimise this as ‘work’, and not as paid rape– unionising would not help these women, as it isn’t just about poor working conditions; often, attempts to unionise are in line with what the pimps and brothel runners want”. On this subject, the author severely undermines her own argument by placing herself firmly in the tradition of radical feminism which she aims to critique. While this article was the catalyst for me to finally get off my ass and write about this issue which I have spent so much time reading and learning about, I am well aware that this type of rhetoric is not limited to this author, nor necessarily endemic to the YCL at large. Indeed, I know that similar perspectives on sex work persist even among members of the CYM. Rather, I find it to be representative of a larger failing (or perhaps refusal?) among non-sex working communists to engage meaningfully with the growing global movement of sex worker-led activism, and to understand that the fight for sex worker rights is a fight against the exploitation of women.

The repetitive arguments around sex work that swing back and forth between rigid dichotomies like “empowerment” vs. “exploitation” and “victimhood” vs. “agency” are for the most part hugely unproductive and operate largely in service of capital. There is a contingent of communists and socialists that take a strong “anti-prostitution” or “abolitionist” stance, believing the sex industry to be a site of immense exploitation and gendered violence which should not continue in its current form (a fact with which I do not disagree). These discursive battles about sex work have raged between feminist factions for decades, but it is disappointing to see that so many communists still cling to a position on these issues which is devoid of nuance or critical Marxist feminist analysis, dismissive of harm reductionist approaches, and, above all, refuses to learn from or show solidarity with sex workers. It is especially frustrating to see this kind of rhetoric among “sex work abolitionist” men on the left, who often seem less interested in trying to understand the complexities of feminist struggle than in vying to outdo one another in a contest of Who Hates Porn, And Thus Respects Women, The Most.

What are the facts?

I think many communists would be able to agree on certain statements about the sex trade. Most people who sell sex are trans and cis women, although nonbinary trans people and men form a significant minority. Most people who begin to sell sex do so because they need to make more money in order to survive and have better options. Those working within the sex trade face, to varying degrees, threats of exploitation, theft, and physical violence. Where we seem to disagree is on the question of how best to address the fact that the sex industry is so exploitative and dangerous. Some strongly support sex workers’ collective organisations and unionisation, some do not. Some support an abolitionist or neo-abolitionist legal model (for example, the “Nordic model”), which criminalises clients and third parties while supposedly decriminalising the worker. Some support decriminalisation of sex work. Some shy away from endorsing any legal model, preferring to focus on theoretical arguments over whether sex work will exist (or need to exist) “under socialism”, or whether it can be classed in a Marxist sense as productive, reproductive or even “socially necessary” labour. On this topic I am inclined to agree with Marxist feminists before me who problematise the “social necessity” of labour in general, and interrogate frameworks which maintain productive and reproductive labour as distinct spheres (see Heather Berg on “(Re)Productivism and Refusal” and “Discourses of Labor” for a more critical analysis than that which I am able to offer here). I think it is also worth noting the arguments against understanding sex work as reproductive labour due to its lack of “social necessity” are deeply flawed and fundamentally conservative and stem primarily from the work of a certain radical feminist who, like many anti-prostitution feminists, is also massively transphobic – so you might want to reconsider using those talking points as a theoretical basis for your analysis of women’s oppression given that they share an ideological groundwork with a whole host of repulsive corollaries. We can, for example, have “after the revolution” conversations as much as we want (sex workers, too, are having them!), but I think we are being deeply irresponsible if we simultaneously refuse to engage with people in the here and now. Whether you like it or not, people are selling sex, people will continue to sell sex at least as long as they need to do so to survive, and as long as they see it as the best option available to them. You cannot wish away sex work, even if you want to.

There are a huge number of factors at play that determine the severity of the threats faced by sex workers; workers of course are well aware of this and make decisions in order to mitigate harms when they can. That is to say that sex workers know what makes them more or less safe. As we (should) engage with any community or group of workers seeking to organise collectively for justice, we would do well to learn from sex workers when they speak about their experiences and what it is they want and need. How can we claim to have a comprehensive, nuanced, or in any way correct analysis of sex work– or indeed, of patriarchy and gendered violence, migration, or austerity– while we refuse to respect those most directly affected?

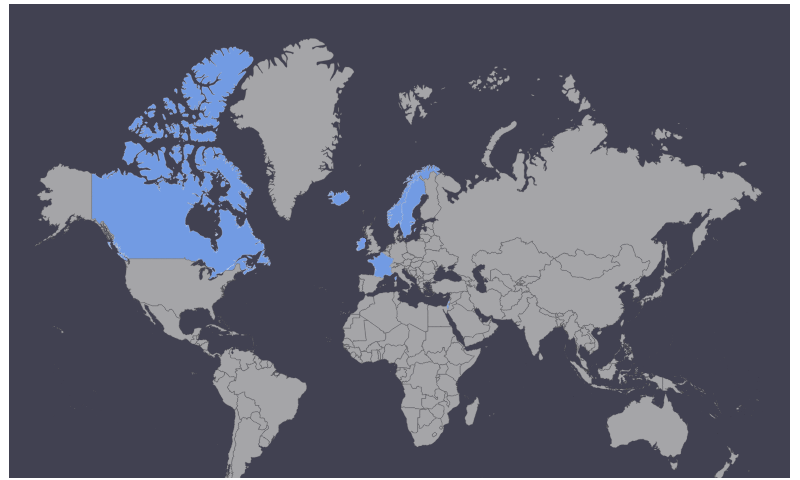

Obviously sex workers are not a monolith and may hold diverse views on any given issue. There is no one single universally representative experience of sex work. It is also true that the vast majority of sex worker-led organisations, and many individual workers (whether or not they might consider themselves activists), in dozens of countries across six continents, are united in their call for the decriminalisation of sex work. Many of these groups and individuals maintain that the dangers of sex work stem from the criminalisation and stigma surrounding it rather than the work itself.

The End Demand Model is a Dead End Model

To advocate policing as a solution to violence is to ignore the basic fact that the police are perpetrators of that violence, both individually and systemically, and that giving the police more power to harass workers is not the answer to anything. Cops will never help sex workers as long as they know they can profit off of raiding them and stealing their earnings, assault them without facing consequences, and all the while be held up in the press and the public eye as heroes who are saving vulnerable young women from a terrible plight or clearing our streets of immoral filth.

People who sell sex engage in safety strategies to mitigate the dangers they face, be they from clients, bosses, cops, or the state. Criminalisation of their existence– their occupation, their legal status, their drug use, their living situation, their behaviour– including through ostensibly progressive laws like sex purchase bans or anti-trafficking legislation, make these safety strategies difficult or impossible. Many so-called “abolitionists” uphold sex purchase bans, also called the Nordic, Swedish, or End Demand model, as a progressive and feminist approach to eliminating prostitution. This model ostensibly removes the burden of criminalisation from the worker and places it onto clients and any third parties. In reality, it doesn’t work like that. In the 26 counties, the majority of people charged under this law since it took effect in 2017 have been migrant women charged with “brothel keeping” simply because they work together in the same residence. Any laws criminalising prostitution or other forms of sex work are used primarily as a tool of violence and control over those most marginalised, especially trans, black, homeless, and migrant women who sell sex. The law will always come down hardest on those who hold the least power under capitalism.

When you are criminalised, you are under constant threat. You cannot report a bad boss or client to the police when they are that bad client or boss, and even if they aren’t, the police are still able to blackmail and brutalise you with impunity. Under full or partial criminalisation models, police can raid your workplace and put you and your colleagues out of a job with no alternatives; or charge you with keeping a brothel and confiscate all the money you have on hand simply because you work together with a friend in the next room; or charge your friend, partner, or relative with pimping or trafficking you because they do secretarial work for you, gave you a lift, or let you crash on their couch. Even under the supposedly progressive, feminist “end demand” model, the state still has the power to arrest, incarcerate, evict, deport, and remove child custody rights from sex workers. These models are aimed at targeting and disempowering workers by depriving them simultaneously of self-agency and the ability to seek help from civil authorities.

Harming workers is not just incidental but inherent to the Nordic model’s design. Foundational to this criminal model is the fact that it aims to make selling sex more difficult and more dangerous. The idea is that by targeting the supposed “demand” for commercial sex, the “supply” will thus decrease, people will simply stop selling sex, and we will then have a world free from the exploitation and violence that occurs within the sex industry. But what is crucial (and what shouldn’t be difficult for socialists to understand!) is that people work because they need money, and sex work is no exception. It might even be more useful to understand the true “demand” for sex work might not be the clients so much as the expenses that workers have to cover, which may include rent, bills, childcare, sending money to family in another country, or paying for expensive criminalised drugs. The Nordic model of criminalisation seeks to eliminate this source of income for people, many of whom have few other options and might have any number of reasons why they are unable or unwilling to access governmental aid or outreach services, let alone simply get a different job outside of the sex industry. Additionally, criminalising the client can actually put the worker in more danger, not less. As sex working activists and authors (and self-identified communists) Juno Mac and Molly Smith explain:

[When you criminalize the client, that pushes sex workers to] try and protect the client, because they need the transaction. So, they protect their income by protecting the client, and protecting the client looks like keeping them away from the police, which might look like working in a more remote location, taking risks. And if the client identifies that the sex worker is doing that, that puts him actually in a position of power, which is the paradox of criminalizing the client… There is some asymmetry in the model, but it’s not the asymmetry that feminists imagined, it’s the fact that the sex worker is gonna compromise what they need and want in order to give the client what he wants… because at the end of the day the bottom line is the sex worker needs to eat.

End Demand’s Promised Services are Inadequate

The other side of the “end demand” model, what is supposed to make up for the increased danger and precarity it causes, is an increase in services available to sex workers, especially to help them leave the industry. The fact is that in countries where this type of model has been adopted, these services are meagre, and come nowhere near replacing the income one would otherwise earn selling sex. The quality of most of these “services” is also a huge problem. Sex workers report facing judgment, condescension, and harassment from staff of certain “support” organisations, especially when those workers don’t fit that organisation’s constructed image of the “victim who is harmed by prostitution”. Additionally, many of the existing or proposed supports are only offered to people who have already stopped selling sex, or “exited”. There are a multitude of reasons why people can’t or won’t stop selling sex before their needs are met, or feel they cannot afford to make themselves more visible even to outreach or support services. That is to say that these “services”, as they exist, are woefully inadequate, and many people cannot and will not avail of them to “exit” the industry, even when sex work becomes increasingly difficult and dangerous. Are we okay with leaving these people to become more and more destitute, forcing them to increasingly compromise their own safety out of desperation, until, what– they die, and we no longer have to worry about them? Or they wake up one day and suddenly see the error of their ways and just go get a straight job? Removing their income and making their lives harder does not mean they will suddenly become able to change their immigration status, or stop needing to pay for drugs, or become mentally and physically capable of meeting the requirements of many legal jobs, or be able to care for their children and their disabled relatives while working full time, outside of their home, for minimum wage. If you claim to give a shit about sex workers’ humanity, you should see it as glaringly unacceptable to treat them as disposable.

Catholic Faith is still at the heart of Regressive “Left” Policy in Ireland

Besides, who are we trusting to provide these services? The government? Our governments, which have never shown any empathy with poor women, which seem to relish in making their lives harder at every turn? The government in the 26 counties already largely outsources mental health support to the private sector and charities (many of which do not treat people with severe mental illness), and is replicating that privatised charity model with sex worker services. The Justice Department and the HSE currently provide funding to only one organisation that focuses on sex worker outreach, despite evidence that far more sex workers seek the services of other groups, namely Ugly Mugs IE and Sex Workers Alliance Ireland. That organization is Ruhama, one of the most prominent “anti-prostitution” and “anti-trafficking” groups in the country, who were instrumental in the “Turn Off The Red Light” campaign which successfully lobbied for the implementation of the sex purchase ban in the 26 counties in 2017. This is a direct continuation of the state’s catholic tradition and policy agenda in the 20th century. Ruhama is a Catholic organisation run by the same orders which ran, and continue to profit off the sites of, Magdalene laundries. It is, to put it lightly, difficult to imagine an organisation like this truly having marginalised women’s best interests at heart. The “end demand” model finds support among cops, conservatives, the Church and the religious right, and transphobes who dare to call themselves feminists. Are proponents of the “end demand” model truly concerned about the lives, safety, and humanity of sex workers, or is there something else at work here? If you want to provide services and resources to people, why not just do that, without simultaneously trying to make their lives harder, or giving more power to the police?

It is abundantly clear that from Sweden to France to all 32 counties of Ireland, the Nordic model has had the effects sex workers warned it would: an increase in the violence, insecurity, and stigmatisation workers face; with no measurable decrease in “trafficking” or in the number of people selling sex, and very little manifestation of promised support services. The Nordic model aims to make it as difficult as possible for people selling sex to make the money they need to live. We must not accept that workers who do not or cannot just stop, and are thus more vulnerable to all forms of violence under this model, are to be viewed as some sort of collateral damage in a larger war against women’s oppression. Criminalisation cannot be relied upon as a tool to end violence against women. As Juno Mac states, “To abolish the sex industry can’t happen so quickly that the people who still depend on it to survive are just cannon fodder.” There is nothing new, nothing the least bit progressive or feminist about hating sex workers or believing you have a better understanding of their work and lives than they do.

Decriminalisation Is a Unifying Demand

It is unethical to advocate for the abolition of sex work using the methods of the capitalist, carceral state. People who sell sex– especially those who are, for example, trans, disabled, racialised, homeless, migrants, and/or drug users– have few options. What they need is not to have the best of those options snatched away from them. The best thing we as non-sex working organisers, communists, and people, can do is to learn from workers and act in solidarity. Sex worker-led organisations exist all over the world in the form of collectives or labour unions, mutual aid networks, and advocacy groups. Many provide resources, information, and support for sex workers as well as educate non-sex workers, influence policies and public opinion, and generally fight for a better world. One demand in common among most if not virtually all sex worker-led organisations is the full decriminalisation of sex work.

Decriminalisation seeks to divest power from the police (as well as from clients, exploitative managers, the state, and other profiteers) and return power to (sex) workers. Advocates of decrim assert that any sort of criminalisation compounds the threat of violence to sex workers. Decrim stands in drastic contrast to all models which seek to abolish or control the sex trade by means of the carceral state, whether in the form of sex purchase bans, full criminalisation, laws against brothel-keeping, immigration restrictions, partial legalisation where certain forms of sex work are highly regulated and others remain criminalised, or “anti-trafficking” legislation like SESTA/FOSTA in the US which aim to remove the ability for workers to advertise on online platforms. Sex workers need to be able to work together, indoors or out; to screen clients and maintain online “bad date” lists to share amongst each other; to advertise for themselves rather than relying on managers to find clients for them; to access services without risking being criminalised. Decriminalisation is an important step in tackling the entrenched social stigma against sex workers which can prevent them from, for example, renting accommodation, accessing proper health care, or joining their local union. This intense stigma also puts sex workers at greater risk of physical violence. It enables sex workers to centre their own narrative, managing and negotiating for improved pay and conditions from a position of strength.

Decriminalisation is a gateway to a Broader Struggle

Decriminalisation is not a magic wand that will itself put an end to violence or exploitation but it is an absolutely necessary step towards ensuring safety and security for people who sell sex. There are valid critiques and important conversations that are being had around the scope and limitations of decriminalisation. For example, in Aotearoa (New Zealand), the first country to decriminalise sex work, immigration law means that many migrant sex workers continue to be criminalised. This speaks less to the failures of decrim than to the need for collective struggle for migrants’ rights, a struggle which many sex workers are already engaged in. Few activists’ work or goals start and end with the need for decriminalisation. Sex workers understand deeply the need for collective struggle against racism, misogyny, and capitalism; the need for workers to organise across occupations in pursuit of a better world. As author, erotic labourer, and SWOP board member Femi Babylon writes (@thotscholar on Twitter), “Decriminalization will not automatically give erotic laborers labor rights and protections. Because of how labor laws have eroded over the past few decades, hence the rise of the gig economy, we will need to join forces with other groups of workers and fight for labor justice”. The English Collective of Prostitutes summarises the situation thusly:

The criminalisation of sex work cuts sex workers off from the ways other workers have found to organise to improve their working conditions. Even basic protections such as the ability to work with others are denied to sex workers, let alone the right to join a trade union and organise collectively, go on strike and protest against our work when it is exploitative and abusive.That is a key motivation for the international sex worker-led movement to demand the full decriminalisation of sex work.

What the decriminalisation of sex work in the UK and internationally would also do is strengthen sex workers’ struggle against exploitation by connecting it with other workers fighting similarly for the right to refuse “bad” jobs and for alternatives in a world where the 99% have to do waged work to survive.

Decriminalisation should be a baseline from which to advance struggle, yet so many communists refuse to support even this very basic measure which will materially improve the lives of some of the people most harmed by capitalism. It is just not good enough for non-sex working communists to dismiss decriminalisation as a liberal demand and therefore not worth fighting for! As Molly Smith puts it:

“I don’t agree that it’s liberal… because I think that really underplays how radical it is to come into a politics where you explicitly foreground prostitutes’ safety as incredibly important– like, that is so radical”.

It is frustrating to see communists continually fail to support sex workers in their specific struggles, and dismiss their demands as liberal, because so many sex workers understand their fight to be a necessarily anticapitalist one. There are so many sex workers all around the world who educate, agitate, and organise for sex workers’ rights; for migrants’ rights; for trans and queer liberation; for an end to police violence and the carceral state; for high-quality public housing, healthcare, and childcare; for stronger labour protections; for compassionate approaches to drug use and treatment.

The Struggle for Sex Workers’ Rights is Radical

Beginning on June 2, 1975, sex workers in France occupied churches for eight days to protest poverty, fines, and police harassment. In 1977, when sex workers in San Francisco were organising against police crackdowns and increased fines, groups affiliated with the Marxist feminist “Wages for Housework” movement published powerful manifestos in support. These groups, including Black Women for Wages for Housework and Wages Due Lesbians, among others, understood the need for all women to come together in solidarity with sex workers. The English Collective of Prostitutes recently released a report comparing the pay and conditions of sex work with other types of (mostly waged) labour performed disproportionately by women, which dispels– or at the very least problematises– the idea that sex work is uniquely exploitative. Trans sex workers of color have been at the forefront of the fight for LGBTQ+ liberation for decades. TAMPEP, a migrant sex worker-led advocacy network across Europe, opposes the criminalisation of migration and health status in addition to sex work. Durbar, a collectivised network of sixty-five thousand sex workers based in India, “seeks to build… a new social order where there is no discrimination by class, caste, gender or occupation”. SWOP Behind Bars in the United States supports criminalised sex workers and fights for the rights of incarcerated persons. Many sex worker activists call for a re-examination of the predominant rhetorical and legal frameworks around “trafficking”, and for a redistribution of resources (and moral high ground) away from cops, conservatives and the rescue industry, and back into the hands of workers and marginalized communities. Sex workers are in the streets right now protesting for Black liberation and an end to all police and state violence.

In their book Revolting Prostitutes, Juno Mac and Molly Smith write in their poignant opening paragraph, “Sex workers are everywhere. … Sex workers are incarcerated inside immigration detention centers, and sex workers are protesting outside them”. There is no political or social issue which does not affect sex workers, and no struggle for justice in which sex workers are not participating. We cannot in turn refuse to struggle alongside sex workers against the specific injustices they face.

To work towards a better world, we must take our cues from the people who are most affected by the exploitation and oppression of capitalism. If we understand that poverty and austerity push people into sex work, we must see sex workers as valuable allies in fighting poverty and austerity. Surely we should be more horrified by the numbers of people plunged into destitution than the numbers of people who choose sex work as a means of refusing that destitution.

Against Both the Ultra-Leftist and the Liberal Deviation

All this is not to say that there is no validity to certain accusations of liberalism against pro-sex worker activism. It is not altogether uncommon for sex workers and their allies, especially in online spaces which don’t lend themselves to exploring nuance, to resort to arguing that sex work is intrinsically noble and empowering and free of coercion, or trying to draw a definitive line between those who are trafficked into the sex trade and those who freely choose their work, for example. Some people discuss and support sex work in a way that is uncritical of capitalism or defend the current form of the sex industry in general or focus on the “rights” of (usually male) clients. Defences of sex work or the sex trade which fail to indict capitalism demand criticism. Sex work is work; that does not mean it is exceptionally good work, or work that is somehow free of the coercive forces of capitalism. Heather Berg suggests that these types of arguments fall into the trap of replicating capitalist logic by attempting to tie workers’ entitlement to rights to the social value of their occupation, thereby “reinforc[ing] a work ethic discourse that locates personhood in one’s contributions to systems of value production”. In this sense, it is no different to the “Right to Work” narrative that American capitalists used to force workers into poorer conditions. Much mainstream sex worker activism also has a tendency to centre white, middle class, cis women in their frameworks and reconfiguration of the sex worker subject. While none of these issues provide an excuse to dismiss or condemn the fight for sex workers’ rights, they must be taken seriously.

Whatever your stance, it is both possible and necessary to have some understanding of where your opponents’ arguments are coming from. To their credit, many people who take either radical feminist or liberal feminist stances on prostitution, porn, or other forms of sex work may have their heart in the right place. It is understandable to see the vast amount of exploitation and violence faced by so many people who sell sex, and to want it to stop. You might be aware of the ways in which capitalism complicates consent and the coercive forces that influence people’s choices and experiences, problematising the idea that you can truly be “free” to choose your work (an issue which is not limited to erotic labour). “Abolitionists” may simply want to live in a world where no one has to sell sex in order to survive, where everyone has the resources they need and we all take care of each other. Sex workers share this dream; as Molly Smith says of these “abolitionists”, “Maybe they want to fight for a world where no one is facing destitution, and that’s great, like, sex workers will join them in that fight. But you’re not gonna achieve that by being like ‘oh yeah, we should give more power to the police and to the immigration police’.”

Against Liberal Rhetoric

Likewise, it is understandable that sex workers may adopt liberal rhetoric when so many are, in the words of Juno Mac, “backed into a corner by a world that hates them”. Sex workers have for centuries been depicted in the public imagination as either (or simultaneously) victims or villains, helpless and in need of rescue or hell-bent on the destruction of themselves and everyone around them. Sex workers are criminalised, demonised, stigmatised, and dehumanised at every turn, but rarely are they trusted to be smart, rational people who are capable of caring for themselves and others. Arguments that tie their worth as workers or as people to the perceived social value of their labour, though ultimately reinforcing the existence of categories of “worthy” or “unworthy” labour and behaviour, have achieved results for workers in the short term.

Many people, in aiming for women’s liberation, end up supporting the police or supporting capitalism as proposed solutions. It is possible to move beyond both these reductive approaches. We can strive to honor the dialectical relationship between the coercive forces of capitalism and people’s agency to struggle against those forces. Katie Cruz argues that it is more useful to understand migrant sex work in particular as “existing along a continuum of (labour) unfreedoms”, an analysis which can be extended to encompass all sex work, and indeed perhaps all work, and all migration. This framework allows more space for solidarity and action between workers. With regard to human trafficking, for instance, we do not have to conflate all sex work with sex trafficking, and thus further bolster the multi-billion dollar “anti-trafficking” industry to continue their harmful (and ineffective) crusade against human trafficking. We also do not have to attempt to somehow draw a clear line between people who migrate and/or sell sex freely and those who are trafficked. Understanding all work as existing on this spectrum of unfreedom under capitalism allows for all of us to come together and struggle collectively for control over our lives and labour. It allows space for recognising how the forces of capital shape people’s lives in various coercive ways, as well as honoring people as rational actors who try to make the best decisions for themselves given their circumstances.

In clarifying this understanding of (un)freedom, Katie Cruz writes, “Freedom within capitalist social relations cannot exist because we cannot reproduce families, communities, and ourselves without access to a wage. ‘Free’ labour, then, is characterised by the limitation of labour unfreedom. It exists where waged and unwaged labour is embedded in a system of labour and social rights and protections… Unwaged labour protections include, for example, access to childcare, eldercare, abortion, healthcare, and affordable housing and food. At the same time, Marxist feminists insist that freedom will entail ending the capital-labour relation (and hence all forms of labour exploitation and alienation) such that we can have meaningful collective control of our labour and lives.” This Marxist feminist analysis aligns with many anticapitalist sex workers who believe ultimately in fighting for a world where our survival, our ability to care for ourselves and each other, is not dependent on earning a wage.

The Struggle is Just Beginning

Communists see the need for workers to join trade unions in order to struggle collectively for labour protections and freedoms within capitalism, and ultimately to struggle against capitalism. What is it that prevents so many of us from extending that analysis to sex workers? Would we decline to show solidarity with miners on strike for improved working conditions, on the basis that mining is incredibly dangerous work, or that it has often functioned as a tool of colonial violence? Would we refuse to assist workers in organising at a local meatpacking plant because we don’t want to “legitimise” the factory farming industry? Contrary to those who push this idea that the unionisation of sex workers specifically is somehow bad for the workers and good for their bosses, many sex workers who are unionised find that it gives them more power, not less, in their dealings with bosses, clients, and police.

Now is as good a time as any to recognise sex workers’ pride of place in the labour movement (and not to treat them as though we are helpers or saviors), especially as the pandemic has thrown existing power imbalances, the desperate precarity of so many workers, and the utter failures of capitalism into sharp relief. People employed in the sex industry and many domestic care workers, for example, especially migrants and those who are employed informally, are among a significant number of people who do not have access to (already meagre) emergency government aid. While current conditions are exacerbated by the pandemic, the steady erosion of labour rights and protections is no news to socialists. In this sense the labour movement at large would do very well to center the voices of sex workers, because as Katie Cruz contends, “sex workers have never had and lost (labour) rights. It is therefore more instructive to see the organisation of paid social reproduction (and indeed paid labour in general) emulating the precarious conditions that have always prevailed for sex workers”. The rise of the gig economy, zero-hour contracts, and other conditions that make workers more precarious and less able to rise against their own exploitation mirror the reality sex workers have always known. Workers in all sectors have a lot to learn from sex workers! In the words of Lorelei Lee (@MissLoreleiLee on Twitter), “Centering people in the sex trades in labor movements means recognizing the vast knowledge sex workers have of risk mitigation, of developing radical survival strategies, of negotiating oppressive labor systems without institutional support– knowledge needed by all workers”. At a time when many people are engaging in crucial mutual aid projects for perhaps the first time, many sex workers are used to practicing mutual aid as a matter of survival, when so few non-sex workers are willing to lift a finger to offer more than moralising. As Magpie Corvid points out, “Surely we could do even more to improve our working conditions if police and society stopped targeting us.” Sex workers engage in all types of paid and unpaid labour, and participate in all types of social struggles whether they are explicitly welcomed or not. They cannot continue to be excluded from the labour movement at large, nor from ostensibly Marxist and socialist feminist analyses of capitalism and patriarchy.

Conclusion

Communists and other socialists need to rethink how we have historically and, in many cases, continue to regard and treat sex workers. We need to closely examine the ways our perspectives on sex work and workers may be influenced by centuries of insidious societal stigma against people who sell sex, a stigma in which the forces of capital are deeply invested. We cannot condemn violence against women or declare our concern for people who face harm while doing sex work, and also refuse to openly support measures like decriminalisation which will – immediately, materially- give people more power to keep themselves and each other safe. To claim that sex workers’ unionisation “won’t help” because “it’s not just about poor working conditions”, implying that better working conditions aren’t worth fighting for, is unspeakably cruel when you consider that for a sex worker, better working conditions might mean you are exponentially less likely to be murdered while working tonight. To state that all prostitution is inherently rape is to treat all sex workers as victims in need of rescue rather than people fighting for a better life; it also makes it impossible to meaningfully support those who have been sexually assaulted or raped and who understand that specific violence as different from their usual experiences of sex work. It’s not good enough to talk about the harms of trafficking without examining the ways in which discourse and legislation around trafficking bolsters police power, immigration restrictions, and conservatism. Stigma and hatred against sex workers is deeply ingrained, and communists are not automatically immune to perpetuating this stigma – we must continually interrogate and critique ourselves as we should with any persistent reactionary tendencies, such as transphobia. We must move forward by not just including but centring sex workers in our organising and in our ideological frameworks. As Black Women for Wages for Housework declared in 1977, “When prostitutes win, all women win”. An injury to one is an injury to all!

At our latest Ard Fheis (Congress) in February, the CYM passed a motion to form a working group in order to research, develop our analysis, and create educational resources around the topic of sex work and sex workers’ rights. This group is in the process of being formed and I look forward to the work we will be doing. I am hopeful that as we continue to struggle together towards a better informed politic, and towards a better world, we will not disregard the work of transnational anti-capitalist sex worker activists. We cannot effectively oppose capitalism or the patriarchy while attacking or punishing sex workers. To fight for sex workers is to fight for all women, all workers, and everyone who is harmed by capitalism.

As Juno Mac reminds us, “It’s radical when you value sex workers’ lives. Some people can’t and won’t make that the center of their politics, but, obviously, that’s callous.”

What might it look like for us to centre sex workers’ safety and sex workers’ lives in our politics?

***

Many sex worker-led advocacy and support groups have set up hardship funds to send money directly to workers in need. These are just a few; research groups that are local to you.

Please donate!

Sex Workers Alliance Ireland: https://swai-hardship-fund.causevox.com/

Sex Worker Advocacy and Resistance Movement: https://www.swarmcollective.org/donate

Umbrella Lane (Scotland): https://www.justgiving.com/campaign/UmbrellaLaneEmergencyFund

***

Sources, suggested reading and further resources:

Juno Mac and Molly Smith, Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights

Katie Cruz, “Beyond Liberalism: Marxist Feminism, Migrant Sex Work, and Labour Unfreedom”

Heather Berg, “Working for Love, Loving for Work: Discourses of Labor in Feminist Sex-Work Activism”

— “An Honest Day’s Wage for a Dishonest Day’s Work: (Re)Productivism and Refusal”

Magpie Corvid, “Marxism for Whores” https://salvage.zone/in-print/marxism-for-whores/

Laura Renata Martin (introductory text), ‘“All The Work We Do As Women”: Feminist manifestos on prostitution and the state, 1977’ https://www.liesjournal.net/volume1-14-prostitution.pdf

Sarah M., “To the would-be sex work abolitionist, or, ‘ain’t I a woman?’: why are we still having the “feminist vs. sex workers” debate?” https://rabble.ca/news/2012/02/would-be-sex-work-abolitionist-or-aint-i-woman

Sex Worker Advocacy and Resistance Movement (SWARM)

— No Silence To Violence: a report on violence against women in prostitution in the UK https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58cea5cf197aea5216413671/t/5c111cef88251b4b89813501/1544625408442/No+Silence+to+Violence+-+SWARM+Dec17.pdf

— September 20, 2019: “Nordic Model in Northern Ireland a Total Failure: No decrease in sex work, but increases in violence and stigma”

English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP)

— What’s a nice girl like you doing in a job like this?: Comparing sex work with other jobs traditionally done by women https://prostitutescollective.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Nice-Girl-report.pdf

Laura Agustín, Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry

— “Sex as Work and Sex Work: a Marxian take”

— “Migrants in the Mistress’ House: Other voices in the ‘trafficking’ debate”

— “What is Decrim? The many places of prostitution in law”

— “New Zealand prostitution law, sex work, anti-migration and anti-trafficking”

— “Decriminalizing sex work only half the battle: South Africa”

— “The new abolitionist model”

— “The sex worker stigma: How the law perpetuates our hatred (and fear) of prostitutes”

— “Questioning Solidarity: Outreach with Migrants Who Sell Sex”

Kamala Kempadoo, “Women of Color and the Global Sex Trade: Transnational feminist perspectives”

Jo Doezema, “Ouch! Western Feminists’ ‘Wounded Attachment’ to the ‘Third World Prostitute’”

Melissa Gira Grant, Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work

— “The War on Sex Workers: An unholy alliance of feminists, cops, and conservatives hurts women in the name of defending their rights”

Chi Adanna Mgbako, To Live Freely In This World: Sex Worker Activism in Africa

Chi Adanna Mgbako et al., “The Case for Decriminalization of Sex Work in South Africa”

Brit Schulte, “Read ‘Revolting Prostitutes’: Your Socialism Depends On It”

Peter Frase, “The Problem with (Sex) Work” https://www.jacobinmag.com/2012/03/the-problem-with-sex-work/

Sex Workers Alliance Ireland (SWAI)

— “International Workers Day: Sex Work Is Work” https://sexworkersallianceireland.org/2020/05/international-workers-day-sex-work-is-work/

Multimedia:

‘To Survive, To Live’ — a short animated film produced by SWARM for the International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers in 2018 https://www.swarmcollective.org/blog/2019/11/25/film-to-survive-to-live

Stronger Minds podcast, “Breaking Bread– Puttanesca: Sex, Feminism, and Sex Worker Rights with Juno Mac & Molly Smith”

The sex, gambling and drug industry absolutely kills the struggle of labour over capital. That opening quote just shows a liberal nihilism, that you will never bring about emancipation from the class, imperial system so what’s the point.

It’s proper shit when organisations get liberalised so easily, bringing about a socialist economy, a socialist civilisation which has happened before and will happen again is about armed struggle, studying, organising, agitating not about liberalising the economy for people to bring about the comodification of all forms over peoples life.

It’s proper defeatist when an organisation bends the knee too the sex, gambling, drug industry.

I hate how the economy bends us to its will in all forms of life, completely recreates our social being- that’s why I am Marxist-Leninist, Communist because I have had enough of it.

Revolutionary struggle comes when we stand up to that commodification.

This is a refreshingly realistic article on sex work. Thank you so much. I’ve been working in the industry for years. Sex work has helped me escape poverty and it’s been difficult mostly because of the stigma. I always said the hardest thing about being a sex worker was having to be so secretive. It’s hard to be surrounded by your leftist friends while they debate the morality of your job and you can’t even say anything for fear of being discovered.

Go raibh maith agaibh

– sex worker